Article index

To go a story and a testimony

There were many. The most many people were all those who worked in the Bacinella.

Before starting the work, the water in the basin boiled, right? Then he took ... there was a kind of basket with cocoons ...

we had to put the scarf in his head because if not we burned all of us, we wet and there we always went on like this.(Testimony of a Filandera of Landriano (PV) in the video life in Filanda: a story of women.)

The silk thread is produced by the Baco, a small white larva of a moth, which during its short existence feeds continuously and exclusively with mulberry leaves. His life is divided into four mutes, during which the larva grows considerably and changes size and color by taking, in the final phase, a yellowish tone: it is at this stage that the Baco is positioned in the midst of dried sprigs of ginestra or poplar, Prepared if necessary by the breeders and begins to produce a thin and resistant filament that surrounds it by creating the cocoon, a sort of container in which it will complete its transformation becoming a moth. They rarely end their development, because the insect, once an adult, should break the cocoon in which it is locked up to go out outdoors, and in this way it would make the silk wire unusable. Then it is necessary to extract the thread from the cocoon before the insect breaks it.

The silk thread is produced by the Baco, a small white larva of a moth, which during its short existence feeds continuously and exclusively with mulberry leaves. His life is divided into four mutes, during which the larva grows considerably and changes size and color by taking, in the final phase, a yellowish tone: it is at this stage that the Baco is positioned in the midst of dried sprigs of ginestra or poplar, Prepared if necessary by the breeders and begins to produce a thin and resistant filament that surrounds it by creating the cocoon, a sort of container in which it will complete its transformation becoming a moth. They rarely end their development, because the insect, once an adult, should break the cocoon in which it is locked up to go out outdoors, and in this way it would make the silk wire unusable. Then it is necessary to extract the thread from the cocoon before the insect breaks it.

In Northern Italy Filanders, until the middle of the last century, women carried out these tasks. Their work consisted of moving continuously with their bare hands and with the help of Sorcora di Essay, a certain number of cocoons, previously dried in the ovens, in a basin full of hot water. The movement produced the escape of very thin filaments that joined in order to form a single thread, which was then positioned in the Aspo (or Aspa), a machine that enveloped it forming a skein. The threads then had to be scrupulously controlled by women because there was no minimal imperfection.

In Filanda, girls and young girls also worked, who provided to strengthen a certain number of cocoons for the basins and then had to continually collect the residues that were thrown on the ground.

The work of the strengthening was subjected to very severe and daily checks, that is:

the Cal and the Poch , which provided the result of the controls on the quantity of work, which was to correspond to precise parameters.

The pruvìn , which instead established the characteristics of the yarn, that is, the quality of the work of the Fiandera.

The pruvìn , which instead established the characteristics of the yarn, that is, the quality of the work of the Fiandera.

If the final result was not up to expectations, a suspension was applied that went from two to eight days, depending on the lack detected. Or the pay was reduced.

Instead if for some time everything had gone according to the requests, the Filandra could also aspire to a significant increase in compensation.

The work of the women of the Filanders, like so many other works of that era, was extremely tiring, paid very little and harmful to health.

We had nothing, in the evening I went home and went to a small chicken coop to change, to leave things all night because they didn't want me close to me. I always stink. But strong, it was.

The streams worked in large sheds where the humidity rate was very high, in a sultry environment, because the windows had to always remain closed to prevent the air from breaking up the silk wire in the ASPI and to maintain the necessary humidity to the spinning of the silk . Their hands were ruined by the permanence for hours in the water at 70/80 degrees, a temperature necessary to be able to extract the thread from the cocoons. To all this were added the frequent harassment and sexual abuse by the masters.

During work, women were not allowed to chat or speak, but they could sing, because, according to the masters, singing women worked with greater energy and concentration. The singing also had the function of creating union among women and to relieve the effort of work.

"We sang, we took songs and always with that tone of the song we put the words, the words of work, of the spinland".

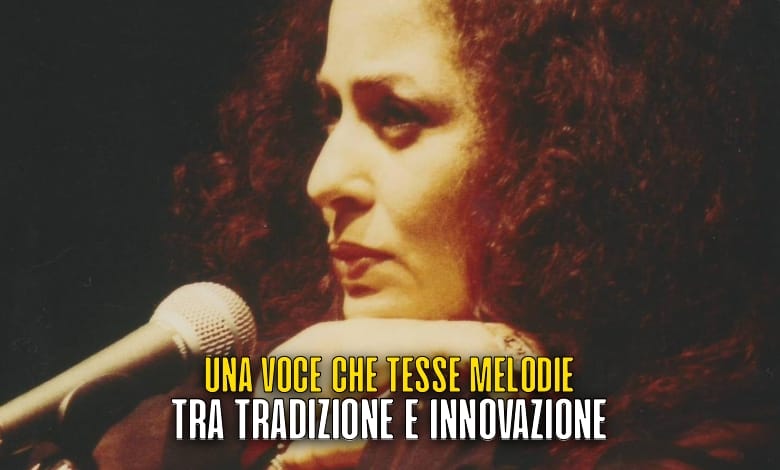

The singing that we propose is a testimony of that life: Mama Mia mi Sun Stove , of an anonymous author, published for the first time in 1940 in the collection of Giacomo Bollini and Attilio Frescura "The Canti della Filanda", old songs of the Brianzole strengthening. You can listen to it below in the version of Anna Identici, an Italian singer who has dedicated himself for a long time to the search and interpretation of Italian popular songs.

And here in the version of Sandra Mantovani, singer and ethnomusicologist, who collaborated with his research to the magazine New Italian Canzoniere, founded in the sixties by Roberto Leydi and Gianni Bosio.

Lyrics of the song

Mama mia, me sun stove

or de Fà the file:

ol cal e ol picch a la Matina,

ol plvìn do voeult a day.

Mama mia, me sun stove

all dì to do the aspa;

I want to go to Bergamo,

in Bergamo to work.

El Mesté de la Filanda

l'El Mesté of the assassins;

poor people those daughters

who are inside to work.

Siam treated as dogs,

like dogs in the chain;

This is not the way

or to make us work.

Tucc me disen che Sun black,

and the is el fumm de la caldera

my love told me

of fa no studs uggo mesté.

Tùcc me Disen Che Sun Gialda,

the ol Filur de la Filanda,

when I will then be in the countryside,

it will return.

Mamma mia, I am tired

of making the filandina:

the cal and the little one in the morning

and the try twice a day.

Mamma mia, I am tired

all day to let go of the row;

I want to go to the Bergamo area,

in the Bergamo area to work.

The profession of Filanda

is the profession of killers;

poor people those girls

who are there to work.

We are treated as dogs,

like dogs in the chain;

This is not the way

of making us work.

Everyone tells me that I am black,

it's the smoke of the boiler;

My love told me

not to make that bad job.

Everyone tells me that I am yellow,

it is the steam of the mill;

Then when I will be in the countryside

my colors will return.

Read also the article: the mystery of the song of women Ainu